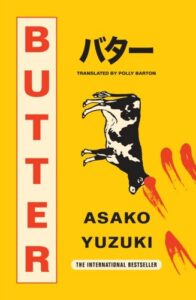

Book Review on Butter by Asako Yuzuki

I am writing this review and questions in preparation for my book club tomorrow. Our choice is Butter (バター (Batā)) by Asako Yuzuki. Well, actually, I chose it, so I feel rather responsible for how it goes down tomorrow.

I am writing this review and questions in preparation for my book club tomorrow. Our choice is Butter (バター (Batā)) by Asako Yuzuki. Well, actually, I chose it, so I feel rather responsible for how it goes down tomorrow.

It was recommended by my daughters, who are both enthusiastic readers and usually a step ahead of me when it comes to discovering new fiction. I began Butter wondering if it might be aimed at a younger audience, perhaps one of those novels that finds fame on #BookTok. I suspect it was, but you will not hear me complaining about that. Asako Yuzuki’s writing is wonderfully accessible yet layered and deeply thoughtful, filled with ideas that linger well beyond any particular age group.

Butter was named Waterstones Book of the Year 2024 and has been widely praised internationally, which is quite an achievement for a translated Japanese novel. In my house, it has sparked conversations about gender, food, power, and the ways women are judged when they do not conform to society’s expectations.

Some of my book club members have already said that Butter takes a bit of perseverance. It is described in some reviews as a slow burner, and I can see why. The pace feels deliberate and controlled. I think it successfully matches the way the narrator, Rika Machida, gradually strips back her own layers of self-control and prejudice as she investigates another woman’s life.

The novel is inspired by the true story of Kanae Kijima, sometimes called the “Konkatsu Killer,” a woman convicted in Japan for murdering men she met through marriage-hunting websites. Yuzuki does not retell that story directly but uses it as a starting point to explore how female guilt is constructed and how quickly public outrage focuses on appearance and morality rather than fact.

In Butter, Rika is a journalist in Tokyo who becomes fascinated by Manako Kajii, a woman in prison accused of killing several men she supposedly charmed through her cooking. Kajii was known for her exceptional food, and when Rika writes to her asking for the recipe to her famous beef stew, an unlikely connection begins. Through their letters and eventual meetings, Rika starts to question not only Kajii’s guilt but her own attitudes toward appetite, ambition, and womanhood.

In part, I found Butter fascinating because it mixes so many genres. It is part literary fiction, part psychological thriller, part social commentary, and also a kind of culinary reflection. The descriptions of food are vivid and symbolic. Yuzuki writes about butter melting, meat simmering, and sauces thickening in ways that feel almost meditative. Food becomes a language of desire, control, and identity, showing what women are permitted to want and what they are punished for wanting too much.

What I also found engaging were the relationships between the women. Rika’s tense memories of her mother, the competitiveness among her female colleagues, and her growing bond with Kajii all reveal how women internalise social pressures and project them onto each other. The friendship between Rika and Kajii evolves from suspicion to fascination, then empathy. By the end, it feels, at least a bit, like Rika has seen a reflection of herself in the woman she set out to condemn.

I have never been to Japan (though I would love to go), so I was curious about how Butter portrays Japanese society and how far off the mark my own insight was. As an older reader, I was struck by how strongly the women characters are still expected to be slim and restrained. It reminded me of Britain in the 1970s and 80s, when similar pressures shaped how women were seen. Reading Butter felt like holding up a mirror between cultures. I was interested in how ideals of discipline, modesty, and self-denial appear in both societies, but I feel I barely touched the surface of the contrasts and comparisons to be had.

One of the most interesting and unsettling aspects of Butter is how much criticism of Kajii focuses on her looks. She is portrayed as fat, plain, and unfeminine, as if those traits prove her guilt. Yuzuki’s choice to highlight this is clever and revealing. The novel suggests that what people really fear is not Kajii’s alleged crimes but her refusal to apologise for existing outside the narrow definition of beauty.

The feminist themes in Butter are quiet but powerful. Yuzuki has said in interviews that she did not set out to expose misogyny, only to portray everyday Japanese life. Yet what emerges is a portrait of how deeply ingrained these attitudes are. Women are expected to be disciplined, modest, and endlessly self-critical, and those who defy that are ridiculed or feared. Rika’s professional composure and Kajii’s unapologetic indulgence represent two extremes of the same societal demand for control.

As I read, I thought about where Butter fits within modern Japanese women’s writing. Years ago, when I taught Japanese literature, I focused on more traditional works such as The Makioka Sisters by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, which explores family life and social class, a kind of Japanese equivalent of Pride and Prejudice. Yuzuki belongs to a newer tradition of women writers who examine the boundaries of conformity within realistic settings, using everyday life to reveal how gender expectations quietly shape experience. Yet by setting her story against the backdrop of a serial killer case, she gives the genre a daring modern twist!

The translator, Polly Barton, deserves real recognition. Translation is always a balancing act, and she manages to keep Butter beautifully readable while preserving its distinct Japanese tone. She retains the cultural flavour of the food and the subtleties of language without over-explaining. Her translation feels natural, allowing the emotional depth and quiet irony of Yuzuki’s prose to come through clearly.

Butter left me thinking about appetite, guilt, and how societies police women’s desires. Why is indulgence so often seen as weakness? Why do we still equate restraint with virtue? And what happens when a woman refuses to shrink herself to fit expectations? The novel does not answer these questions, but it invites readers to sit with them, much like its slow, thoughtful storytelling.

For our book club tomorrow, I expect lively debate. I suspect some will find it slow, others will comment either favourably or critically on its complexity. I think Butter rewards patience. Like the rich dishes described within it, it needs time to simmer and reveal its full flavour.

In the end, I am glad I chose it. Butter is a sensual, unsettling, and quietly radical novel that lingers long after the last page. It made me curious about Japan, reflective about my own generation, and newly aware of how women’s stories, wherever they are set, often share the same struggles and longings.

Book Club Questions on Butter by Asako Yuzuki

- Discuss the friendship between Rika and Kajii. Did you find it believable or strange? How much of it do you think was curiosity, obsession, or something else entirely?

- Discuss which woman in Butter you found the most interesting or layered. Discuss what you found fascinating about her?

- Discuss Rika’s relationship with her boyfriend. What does it reveal about her? Does it make you sympathise with her more, or less?

- Discuss how Rika’s work as a journalist shapes her actions and relationships. How did you feel about the way she was judged for her series of articles, both by others and by herself?

- Discuss how motherhood and care are explored in Butter. How do the women in the novel nurture, or fail to nurture, others and themselves?

- Discuss what Butter shows us about Japanese society and the pressures placed on women. How far do those expectations differ from, or resemble, the ones you’ve seen in your own culture?

- Discuss Yuzuki’s descriptions of food. Did they make you hungry, uncomfortable, or both? What do you think the food represents? Is it comfort, control, temptation, rebellion or something else?

- Discuss the importance and signficance of the cookery school.

- Discuss what you thought of reading Butter in translation. Did Polly Barton’s version feel natural and engaging? Do you think something essential might be lost, or even gained, when a novel moves between languages?

- Discuss the Christmas turkey scene at the end. Why do you think Yuzuki chose that as the closing image? What does it say about Rika’s transformation or her appetite for something new?

- Discuss the interference of Rika’s friend in her relationship. Was it genuine concern, jealousy, or something more self-serving? How did that change your view of both women?

- Discuss the sections that touch on the paedophile? Did it shift how you understood Kajii’s character, or did they make you question Rika’s moral boundaries instead?

Book Club Questions on Butter (for if you haven’t read the book!)

- “There are two things that I simply cannot tolerate: feminists and margarine.” Discuss what you can’t tolerate in life and why. Do you think our dislikes say something about who we are, or are they just quirks of taste and habit?

- Have you read many books in translation? Discuss what might be difficult about the craft of translating fiction.

- Have you ever been to a cookery class? Discuss what the experience was like, and whether learning to cook with others changes how you think about food and sharing meals.

- The main character in Butter moves house and learns to love food in a new way. Discuss your own culinary journey: are you confident in the kitchen, or still finding your way? What do you get from cooking, if anything?