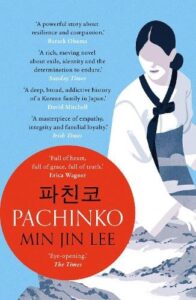

Book Review on Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko

I picked up Pachinko expecting a sweeping family story, and while it certainly is that, it is also something far more penetrating and for me educational. I find the best way to learn about history is through fiction, and from this book I learned an immense amount about life in Japan during the last century and also the role of the immigrant Korean in the society and the traditions and cultures of both Japanese and Koreans. It was a moving read about a country, a people and a century of sorrows, learned by following the stories of ordinary characters and their lives.

I picked up Pachinko expecting a sweeping family story, and while it certainly is that, it is also something far more penetrating and for me educational. I find the best way to learn about history is through fiction, and from this book I learned an immense amount about life in Japan during the last century and also the role of the immigrant Korean in the society and the traditions and cultures of both Japanese and Koreans. It was a moving read about a country, a people and a century of sorrows, learned by following the stories of ordinary characters and their lives.

Having recently read and reviewed Butter and appreciating it much more by knowing a little about its author Asako Yuzuki, I thought it would be useful to learn about Min Jin Lee’s life. She was born in Seoul and raised in Queens, which already suggests she understands what it means to live in between places. She trained as a lawyer but chronic illness pushed her toward writing, and she spent several years researching Korean colonial history and interviewing Zainichi Koreans living in Japan. You can feel her empathy everywhere. In the interviews and the questions and answers at the back of the book, she describes the frustration of having to completely rewrite the manuscript once she moved to Japan and gained a far deeper understanding of what it was like to be an immigrant Korean. Nothing in this book feels rushed or skimmed. It has the weight of someone who has listened carefully. Min Jin Lee says she does not write efficiently, but she writes with certainty and with a commitment to sharing real truth.

The story begins with Sunja, who becomes the firm but gentle centre of the entire saga. She finds herself pregnant as a young woman seduced by Hansu, a wealthy and mysterious older businessman who promises comfort but offers no respect. Refusing to become his second wife, she accepts help from Isak, a kind and earnest Christian minister who offers her marriage and dignity. She takes control of her life and travels to Japan with him, determined to build something more stable for her child. Sunja is practical and fiercely loving, the sort of woman whose strength appears in small and consistent acts rather than dramatic gestures.

Through Sunja’s journey, we step into the world of Koreans living under Japanese occupation and then into Japan itself, where she and her family become part of the community known as Zainichi. I had barely known anything about them before reading this book. They were legally resident but socially excluded, caught in an uncomfortable in between state where they were expected to assimilate yet never allowed to fully belong. The idea that someone could be born in a country, speak the language, work there for decades and still be treated as an outsider sits at the heart of the novel. The exploration of this topic is heartbreaking and the novel never lets you forget the heaviness of that burden.

What struck me most was how differently each character learns to manage that weight. Hansu, the father of Noa, survives by becoming sharper and more calculating than the world around him, and his compromises, however uncomfortable to witness, are shown with nuance. Isak, with his sincerity and gentleness, tries to live by his beliefs and pays a terrible price for it. Their children, Noa and Mozasu, grow into entirely different shapes. Noa attempts to disappear into respectability, hoping he can scrub away the parts of himself that mark him as other. Mozasu embraces the world of pachinko with practicality and pride. It is fascinating to see how two boys raised by the same mother can respond to the world’s cruelty in such opposite ways, one folding himself smaller and smaller, the other standing firm and unapologetic.

I found myself especially moved by the way the novel treats shame. This includes individual shame but also the deep generational shame that families absorb from the outside world. Sunja carries shame for something that was never her fault. Noa’s shame destroys him. Even the Japanese characters feel its grip, with men expected to perform masculinity perfectly and women constrained by expectations they never agreed to. It reminded me of how shame moves through Butter as well. Reading Pachinko after Butter made this even clearer. Both novels portray societies that pride themselves on politeness and restraint, yet that very politeness can obscure rigid and often unfair expectations. In Butter, it is women’s appetites and bodies that are policed. In Pachinko, it is Koreans’ right to belong. They show different expressions of the same instinct, which is control disguised as propriety.

Food weaves through both novels too. In Butter, food becomes indulgence and refusal. In Pachinko, food becomes survival and dignity. Sunja feeding her family during lean years feels as significant as any major plot point. Pachinko itself carries similar weight. It represents chance, stigma, survival, dependence and resilience all at once. It provides economic lifelines while also marking families socially, which makes it the perfect symbol for the tensions the novel explores.

The historical context is essential, but Min Jin Lee never overwhelms the narrative with it. Japan’s occupation of Korea, the land surveys that stole farms, the migrations to Japan and the precarious legal situation of Zainichi Koreans are all present, but only ever through the lived experiences of the characters. You feel the history in their exhaustion, their decisions, the public faces they are forced to wear and the language they choose or avoid. When we reach Solomon in the modern era, it becomes clear that discrimination changes shape but does not fully vanish. The edges may soften but the boundaries remain. The shift to the modern characters makes the book somewhat easier to read, and although I found it slightly less compelling, it is easy to see why this section works so well for television. The generational sweep, the family tensions and the evolving cultural landscapes lend themselves naturally to adaptation, and the scale of the story is perfect for the screen.

What I appreciated most is the compassion the novel shows every character, even the flawed ones. It never mocks their mistakes or simplifies their motivations. Every character is doing the best they can within systems they did not create. It is impossible to read this book without thinking about how many real families lived versions of this story. As I often say, this is how I learn about history, and this novel reminded me once again why fiction can be such a powerful teacher.

I did not love the ending because it felt as though it stopped too suddenly, but even that worked in its own way. It seems to honour the people who lived in the spaces between nations and identities, people whose stories rarely receive neat conclusions. It left me thinking about belonging, luck, sacrifice and all the quiet heroism that goes uncelebrated.

Book Club Questions on Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

- Discuss the relationship between Sunja and Hansu. Did you find their connection convincing, or did it leave you feeling uneasy? What do you think each of them was really looking for?

- Discuss which woman in Pachinko you found the most interesting or layered. What drew you to her?

- Discuss the friendship and partnership between Sunja and Kyunghee. How believable did you find their closeness, and what do you think it reveals about survival, loyalty and love?

- Discuss how gay relationships appear in the novel. How did these moments shape your understanding of secrecy, shame and the risks of being different?

- Discuss Mozasu’s involvement in the pachinko business. What did you learn about the business itself, and how does the industry shape the family’s fate?

- Discuss the symbolic role of pachinko in the novel. What does it come to represent for different generations?

- Discuss Noa’s suicide. How did you respond to the path his life takes, and how far do you think shame and longing for acceptance shaped his decisions?

- Discuss the role of shame in Pachinko. Who carries it, who hides it and who passes it on? Where did you see shame doing the most damage?

- Discuss Isak’s belief system and moral code. How does his goodness strengthen the family, and where does it leave them vulnerable?

- Discuss how motherhood and care are shown in the novel. What moments of nurturing or neglect stayed with you?

- Discuss the portrayal of Koreans living in Japan. Which pressures felt specific to the time and place, and which felt universally recognisable?

- Discuss Solomon’s chapters in the modern era. How did they change your understanding of the family’s story?

- Discuss Hana’s storyline. What does her arc add to the novel’s exploration of belonging, rebellion and loss?

- Discuss the importance of education in Pachinko. How does it shape aspiration and identity?

- Discuss the role of food in the novel. What does Sunja’s cooking come to represent for her and for the people she loves?

- Discuss how community appears in the story. When do the characters feel held, and when are they reminded that they do not truly belong?

- Discuss the structure of Pachinko as a multigenerational novel. How did the shifts through time shape your reading experience?

- Discuss the ending. Did it feel appropriate or unresolved, and what do you think Min Jin Lee wanted you to sit with once you closed the book?

Book Club Questions on Pachinko (for if you haven’t read the book).

- “History has failed us, but no matter” is the opening line of Pachinko, written by Min Jin Lee. Discuss a moment in history you wish you understood better. How do you tend to learn about the past?

- The novel follows a family who migrate and rebuild their lives. Have you ever had to adapt to a new place, culture or community? What stayed with you from that experience?

- Belonging is a central theme. Discuss a time when you felt like an outsider. Did anything help you feel more rooted, or did you stay on the edge?

- Luck matters a great deal in Pachinko. How much do you think luck shapes your own life, and how much comes down to effort or choice?

- Family expectations play a big part in the story. What expectations did you grow up with, and how have they influenced your life?

- The characters in the novel often hide parts of themselves. Have you ever felt pressure to conceal something about who you are or what you believe?

- Food appears throughout Pachinko as a symbol of survival and care. What foods make you feel comforted, connected or at home?

- The novel raises questions about what it means to belong to a place. Do you feel at home where you live now, or does “home” mean something different to you?